William Henry Johnson (circa July 15, 1892 – July 1, 1929), was a United States Army Sergeant, and part of the first African American unit of the U.S. Army to engage in combat during World War I. He was the first U.S. soldier to be recognized with the Croix de Guerre for heroism in France during the war.

Johnson enlisted in the United States Military on June 5, 1917, joining the all-black New York National Guard, 15th Infantry Regiment, which, when mustered into Federal service, was re-designated as the 369th Infantry Regiment, based in Harlem, New York City. The 369th Infantry was under the command of mostly white officers including their commander, Colonel William Hayward.

The 369th Infantry joined the 185th Infantry Brigade upon arrival on in France on New Year’s Day, 1918, but the unit was relegated to labor service duties instead of combat training. The 185th Infantry Brigade was in turn assigned on January 5, 1918, to the U.S. 93rd Division (93rd Infantry Division). Although General John J. Pershing wished to keep the U.S. Army autonomous, in March, he “loaned” the 369th to the 61st Division of the French Fourth Army. The 369th, which would become famous as the “Harlem Hellfighters”, was among the first American troops to arrive in France and the most decorated when it returned.

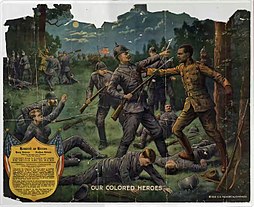

The French Army assigned Johnson’s regiment to Outpost 20, on the edge of the Argonne Forest in the Champagne region of France. They were equipped with French rifles and helmets. While on observation post duty on the night of May 14, 1918, Private Johnson came under attack by a large German raiding party. This party may have numbered as many as 24 German soldiers. Johnson displayed uncommon heroism when, using grenades, the butt of his rifle, a bolo knife and his bare fists, he repelled the Germans, rescuing fellow soldier Needham Roberts from capture and saving the lives of his fellow soldiers. Johnson suffered 21 wounds during this battle. This act of valor earned him the nickname of “Black Death”, as a sign of respect for his prowess in combat.

The story of Johnson’s exploits first came to national attention in an article by Irvin S. Cobb entitled “Young Black Joe” published in the August 24, 1918 Saturday Evening Post.

From 1919 on, Johnson’s story has been part of wider consideration of treatment of African Americans in the Great War. There was a long struggle to achieve U.S. military decorations for Johnson which was also due to his unit being attached to the French Fourth Army in France during the war; Johnson and his men were issued and used French equipment and weapons. Johnson was not awarded the Purple Heart until 1996. In 2002, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism on May 15, 1918, after it was discovered in 2001, that he had been buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Efforts to upgrade the DSC to the Medal of Honor was unsuccessful until June 2, 2015, when he was posthumously presented the Medal of Honor by the President in a ceremony at the White House.